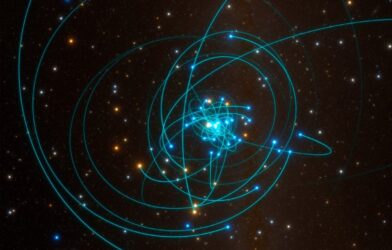

Astronomers are now able to simulate the formation of a cluster of baby stars. A team of international researchers spent two years developing a simulation code that can accurately reproduce the motions of individual stars.

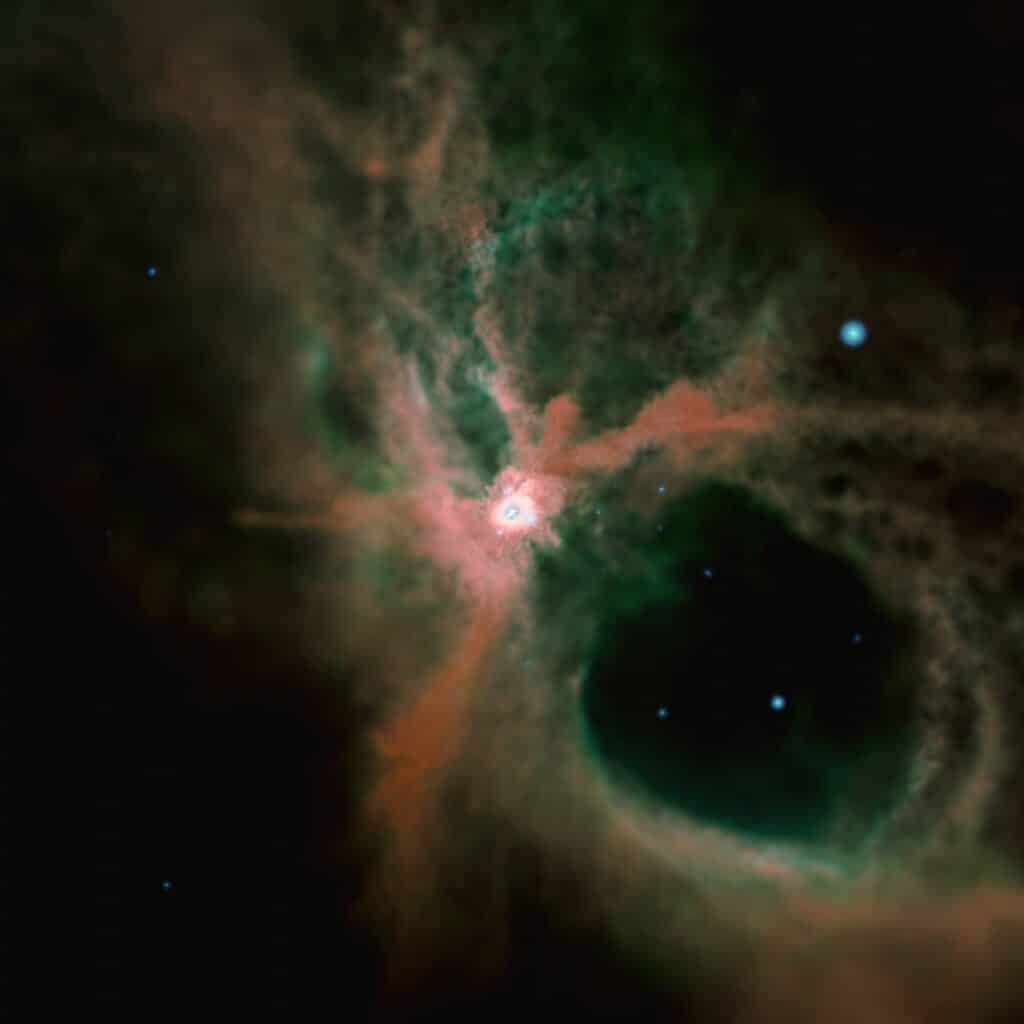

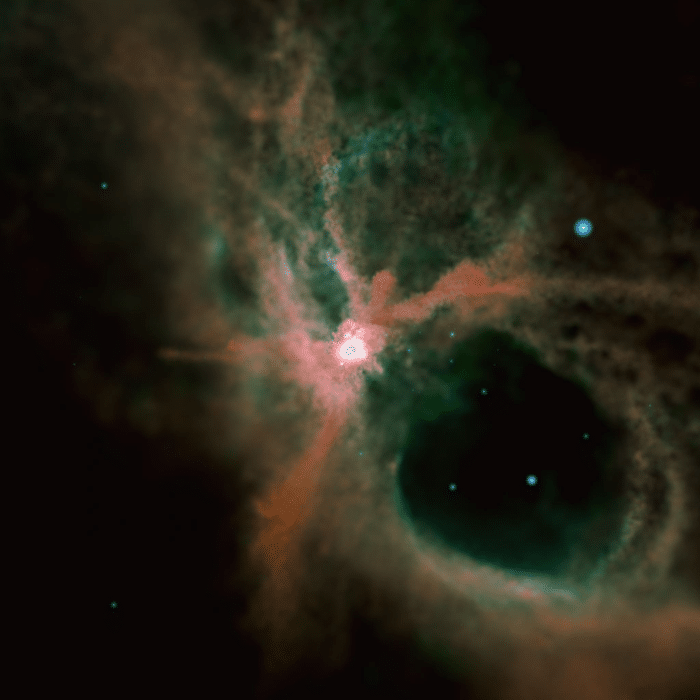

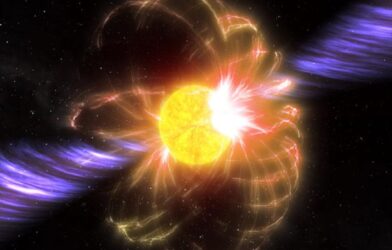

University of Tokyo researchers then simulated a case similar to the Orion Nebula using ATEURI II operated by the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan. They found that the Orion Nebula’s off-centered bubble of ionized gas was caused by a massive star that was pushed out of the newborn cluster, but is now falling back in, similar to that of a yo-yo motion.

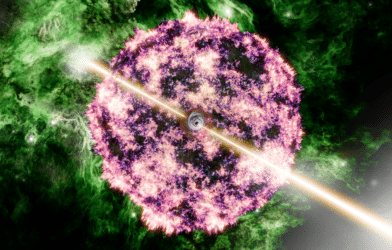

“The velocity distribution of the stars in the simulation matches the result from observations,” says Yoshito Shimajiri, a research team member at the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan, in a statement. “The simulations show that massive, bright, young stars can be ejected from the cluster through gravitational interactions with other stars.”

“Some of these ejected stars run away, never to return,” explains Kohei Hattori, also a research team member at the observatory. “In other cases, like what is observed in the Orion Nebula, a massive star can be thrown a distance from the cluster, where it initiates an ionized bubble, and then fall back into the cluster.”

Star clusters usually form together in clouds of cold hydrogen gas. Since the brightest and largest stars ionize the surrounding gas, it makes it too hot to form new stars. Massive stars essentially shut off new star formation. However, in the Orion Nebula, the ionized bubble is not centered on the most massive stars in the cluster.

“In order to form such off-center bubbles, ionizing light from the massive stars in the cluster must overcome the dense molecular gas in the cluster center and reach the outskirts of the cluster,” the media release reads. Researchers believe these scattered massive stars can punch a hole in the dense molecular gas in the central region to help off-center ionized bubbles get initiated.

“The simulation is not the limit of our simulation code,” says study author Michiko Fujii. “If we use a larger number of CPUs, it can treat even more massive star clusters. Next, we want to undertake the first star-by-star star-cluster formation simulation of globular clusters, which are 100 times more massive than the star cluster we simulated in this study.”

The study is published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

-392x250.png)