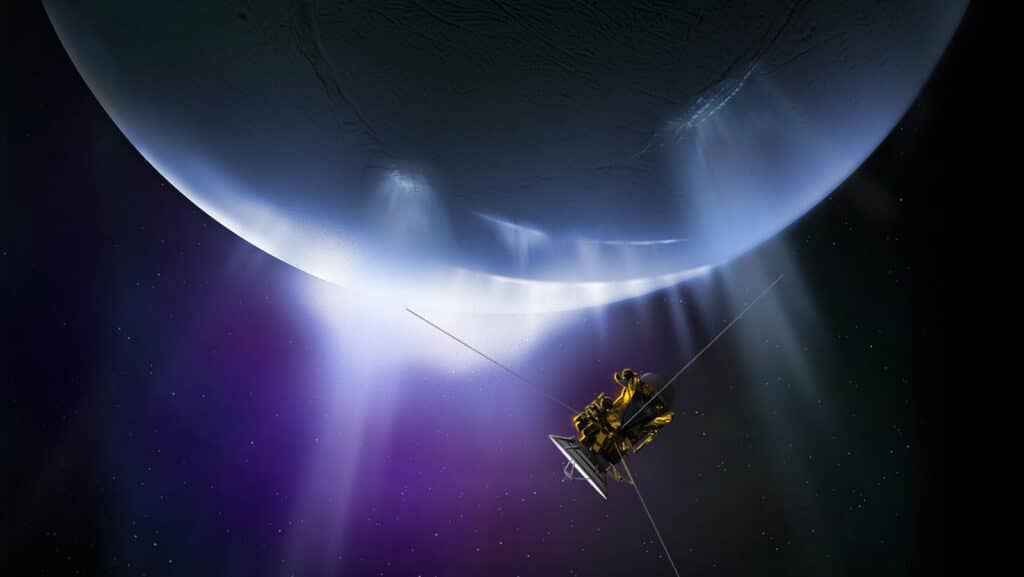

Life could be found on one of Saturn’s moons without a spacecraft even landing on it, according to a new study. Scientists say evidence of life on the icy moon Enceladus could be uncovered by a robot spacecraft sampling plumes jetting out of its liquid interior.

Researchers have long speculated that alien bacteria may live on Enceladus, which is one of the planet’s 83 moons, but they did not have definitive answers. This latest research suggests it could be home to life because it produces methane.

When it was first surveyed by NASA in 1980, Enceladus looked like a not particularly exciting snowball in the sky. A second NASA mission between 2005 and 2017 found its thick layer of ice hides a vast, warm saltwater ocean outgassing methane, a gas that typically comes from microbes on Earth.

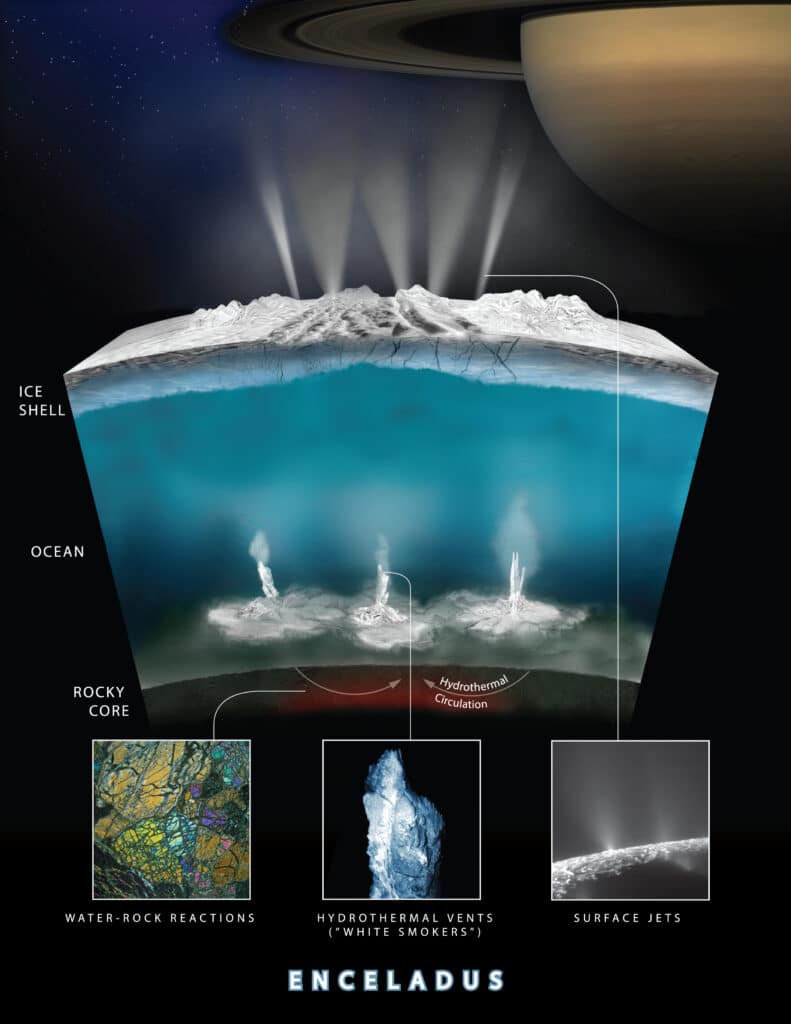

The methane was discovered when the mission’s Cassini spacecraft flew through giant water plumes erupting from the surface of Enceladus. As the tiny moon orbits the ringed gas giant, it is being squeezed and tugged by Saturn’s immense gravitational field, which heats up its interior due to friction.

As a result, spectacular plumes of water jet from cracks and crevices on Enceladus’ icy surface into space.

Last year, scientists from the University of Arizona and Université Paris Sciences et Lettres in France worked out that if life has emerged on Enceladus, this could explain why it is burping up methane.

While the number of bacteria in its ocean would be small, all it would need to uncover them would be a visit from a robot spacecraft.

“Clearly, sending a robot crawling through ice cracks and deep-diving down to the seafloor would not be easy,” says the study’s senior author, Régis Ferrière from the University of Arizona, in a statement. “More realistic missions have been designed that would use upgraded instruments to sample the plumes like Cassini did, or even land on the moon’s surface.

“By simulating the data that a more prepared and advanced orbiting spacecraft would gather from just the plumes alone, our team has now shown that this approach would be enough to confidently determine whether or not there is life within Enceladus’ ocean without actually having to probe the depths of the moon,” Ferrière adds.

Located about 800 million miles from Earth, Enceladus completes an orbit around Saturn every 33 hours. It stands out because its surface is like a frozen pond glinting in the sun, and it reflects light like nothing else in the solar system.

Along the moon’s south pole, at least 100 giant water plumes erupt through cracks in the icy landscape much like lava from a violent volcano. Researchers believe water vapor and ice particles ejected by these-geyser like features make up one of Saturn’s iconic rings.

The excess methane expunged in the plumes resembles hydrothermal vents, which are found under the sea where two tectonic plates meet each other. Where they meet, hot magma below the sea floor heats the ocean water in the porous bedrock- creating “white smokers” which release scorching, mineral-rich hot sea water.

Tiny organisms under the sea have no access to sunlight so they need the energy from chemicals released by white smokers to stay alive.

“On our planet, hydrothermal vents teem with life, big and small, in spite of darkness and insane pressure,” explains Ferrière. “The simplest living creatures there are microbes called methanogens that power themselves even in the absence of sunlight.”

Methanogens convert dihydrogen and carbon dioxide to gain energy and release methane as a by-product.

The researchers’ calculations were based on the theory that Enceladus has methanogens that inhabit oceanic hydrothermal vents resembling the ones found on Earth. The team worked out that the total mass of methanogens on Enceladus would likely be, as well as the likelihood that their cells and other organic molecules could be ejected through the plumes.

The team says that any regions of Enceladus that contain life would feed the plumes with just enough cells or organic materials to be picked up by instruments on a future space ship.

“Our research shows that if a biosphere, a region with living organisms, is present in Enceladus’ ocean, signs of its existence could be picked up in plume material without the need to land or drill, but such a mission would require an orbiter to fly through the plume multiple times to collect lots of oceanic material,” says the study’s first author, Dr. Antonin Affholder, who was at Paris Sciences & Lettres when doing the research.

The team suggests a future mission may struggle to find direct evidence of life but the presence or absence of certain organic molecules, such as particular amino acids, would serve as indirect evidence for or against an environment abounding with life.

“The definitive evidence of living cells caught on an alien world may remain elusive for generations,” says Affholder. “Until then, the fact that we can’t rule out life’s existence on Enceladus is probably the best we can do.”

Scientists now want to go back to Enceladus and one mission proposes to land there in the 2050s to collect “extensive” data about it.

The findings are published in The Planetary Science Journal.

By Gwyn Wright, South West News Service