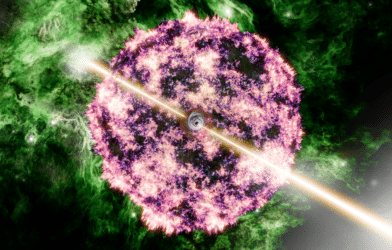

Asteroid 3200 Phaethon has long puzzled scientists with its comet-like behavior. It brightens and forms a tail when it’s near the Sun and is the source of the annual Geminid meteor shower. Previously, scientists believed dust escaping from the asteroid caused Phaethon’s tail. However, new research using two NASA solar observatories reveals that the tail is actually made of sodium gas, not dust.

Qicheng Zhang, the lead author of the study, said in a statement, “Our analysis shows that Phaethon’s comet-like activity cannot be explained by any kind of dust.”

The Difference Between Asteroids and Comets

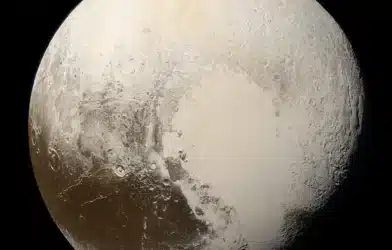

Asteroids, which are mostly rocky, do not usually form tails when they approach the Sun. They can be found primarily in the Asteroid Belt between Mars and Jupiter. Comets, however, are a mix of ice and rock, and typically do form tails as the Sun vaporizes their ice, blasting material off their surfaces and leaving a trail along their orbits. When Earth passes through a debris trail, those cometary bits burn up in our atmosphere and produce a swarm of shooting stars – a meteor shower.

Phaethon’s Connection to the Geminid Meteor Shower

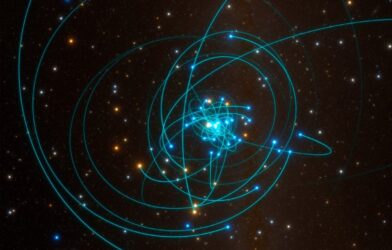

After astronomers discovered Phaethon in 1983, they realized that the asteroid’s orbit matched that of the Geminid meteors. This pointed to Phaethon as the source of the annual meteor shower, even though Phaethon was an asteroid and not a comet. The discovery of Phaethon’s tail in 2009 by NASA’s Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory (STEREO) supported the idea that dust was escaping the asteroid’s surface when heated by the Sun.

However, in 2018, another solar mission imaged part of the Geminid debris trail and found a surprise. Observations from NASA’s Parker Solar Probe showed that the trail contained far more material than Phaethon could possibly shed during its close approaches to the Sun.

Suspecting Sodium in Phaethon’s Tail

Zhang’s team wondered whether something else, other than dust, was behind Phaethon’s comet-like behavior. Zhang explained, “Comets often glow brilliantly by sodium emission when very near the Sun, so we suspected sodium could likewise serve a key role in Phaethon’s brightening.”

An earlier study, based on models and lab tests, suggested that the Sun’s intense heat during Phaethon’s close solar approaches could indeed vaporize sodium within the asteroid and drive comet-like activity.

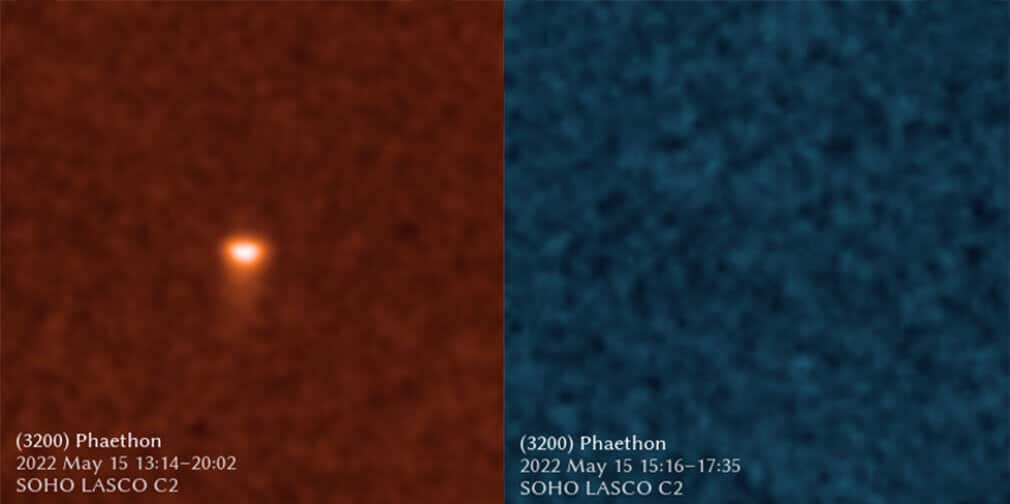

To find out what the tail is really made of, Zhang looked for it again during Phaethon’s latest perihelion in 2022. He used the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) spacecraft — a joint mission between NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA) – which has color filters that can detect sodium and dust. Zhang’s team also searched archival images from STEREO and SOHO, finding the tail during 18 of Phaethon’s close solar approaches between 1997 and 2022.

In SOHO’s observations, the asteroid’s tail appeared bright in the filter that detects sodium, but it did not appear in the filter that detects dust. In addition, the shape of the tail and the way it brightened as Phaethon passed the Sun matched exactly what scientists would expect if it were made of sodium, but not if it were made of dust.

This evidence indicates that Phaethon’s tail is made of sodium, not dust.

A Discovery with Unintended Tools

Karl Battams of the Naval Research Laboratory, a team member, said, “Not only do we have a really cool result that kind of upends 14 years of thinking about a well-scrutinized object, but we also did this using data from two heliophysics spacecraft – SOHO and STEREO – that were not at all intended to study phenomena like this.”

Zhang and his colleagues now wonder whether some comets discovered by SOHO – and by citizen scientists studying SOHO images as part of the Sungrazer Project – are not comets at all. Zhang explained, “A lot of those other sunskirting ‘comets’ may also not be ‘comets’ in the usual, icy body sense, but may instead be rocky asteroids like Phaethon heated up by the Sun.”

One important question remains: If Phaethon doesn’t shed much dust, how does the asteroid supply the material for the Geminid meteor shower we see each December? Zhang’s team suspects that some sort of disruptive event a few thousand years ago – perhaps a piece of the asteroid breaking apart under the stresses of Phaethon’s rotation – caused Phaethon to eject the billion tons of material estimated to make up the Geminid debris stream. But what that event was remains a mystery.

Future Exploration of Phaethon

More answers may come from an upcoming Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) mission called DESTINY+ (short for Demonstration and Experiment of Space Technology for Interplanetary voyage Phaethon fLyby and dUst Science). Later this decade, the DESTINY+ spacecraft is expected to fly past Phaethon, imaging its rocky surface and studying any dust that might exist around this enigmatic asteroid.

Understanding Comets

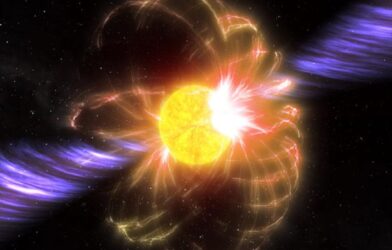

Comets are celestial objects made up of ice, rock, and dust that originate from the outer regions of the solar system. As they approach the Sun, the heat causes their ice to vaporize, creating a glowing coma around the nucleus and sometimes a tail that extends millions of kilometers.

Famous Comets in History

- Halley’s Comet: Named after English astronomer Edmond Halley, who predicted its return in 1758, Halley’s Comet is the most famous short-period comet. It has an orbital period of about 76 years, with its last appearance in 1986 and its next expected appearance in 2061.

- Comet Hale-Bopp: Discovered in 1995, Hale-Bopp was one of the most widely observed comets of the 20th century. It was visible to the naked eye for a record 18 months and displayed a remarkable double tail.

- Comet Hyakutake: This comet, discovered in 1996, had the longest tail ever observed on a comet, stretching over 570 million kilometers. It made a close approach to Earth, providing spectacular views for skywatchers.

- Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9: This comet gained fame in 1994 when it broke into more than 20 fragments and collided with Jupiter, producing dramatic and easily observable impacts.

- Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko: This comet became famous due to the European Space Agency’s Rosetta mission, which orbited and landed a probe on the comet’s surface in 2014, providing unprecedented insights into comet composition and behavior.

The discovery of asteroid 3200 Phaethon’s sodium gas tail has not only challenged our understanding of this unique object but also prompted questions about other sun-skirting comets. The upcoming DESTINY+ mission will provide valuable information about Phaethon’s composition and origin, furthering our understanding of these intriguing celestial objects.

As our knowledge of comets, asteroids, and other celestial bodies expands, so does our understanding of the complexities and mysteries of our solar system. These discoveries remind us that there is still much to learn about the universe and the diverse objects that inhabit it.

Future research and missions will continue to reveal more about Phaethon and other celestial objects, providing insights that help us piece together the history and evolution of our solar system. By studying these unique bodies, we gain a better understanding of the processes that shape the cosmos and the intricate balance that exists between these various celestial inhabitants.

The study on Phaethon’s tail is published in The Planetary Science Journal.

Some of the information used in this article was provided in a release by Vanessa Thomas at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

-392x250.png)