Rocky planets outside the solar system could be even more habitable than Earth, according to new research. They are rich in hydrogen or helium gases, which can support life for almost twice as long. The finding adds to a growing belief that aliens may be common right across the universe.

Our planet has hosted organisms for 3.5 billion years. The sun is slowly brightening and will vaporize water in 1 to 1.5 billion years, so humans will have to leave Earth to survive. Hydrogen- and helium-rich worlds are better suited and could have liquid water on their surface for eight billion years. This would be enough time for sophisticated civilizations to emerge and flourish, say scientists at Zurich University.

The planets would have to be “super Earths,” with a much bigger mass, as hydrogen and helium are lighter than oxygen and escape to space easily. It means any extraterrestrials are likely to look very different, with shorter, stockier builds.

“These planets could keep a temperate surface environment for as long as eight billion years if atmosphere is between 100 to 1,000 times thicker than Earth’s,” says lead author Marit Mol Lous, a PhD student at Zurich, in a statement to South West News Service.

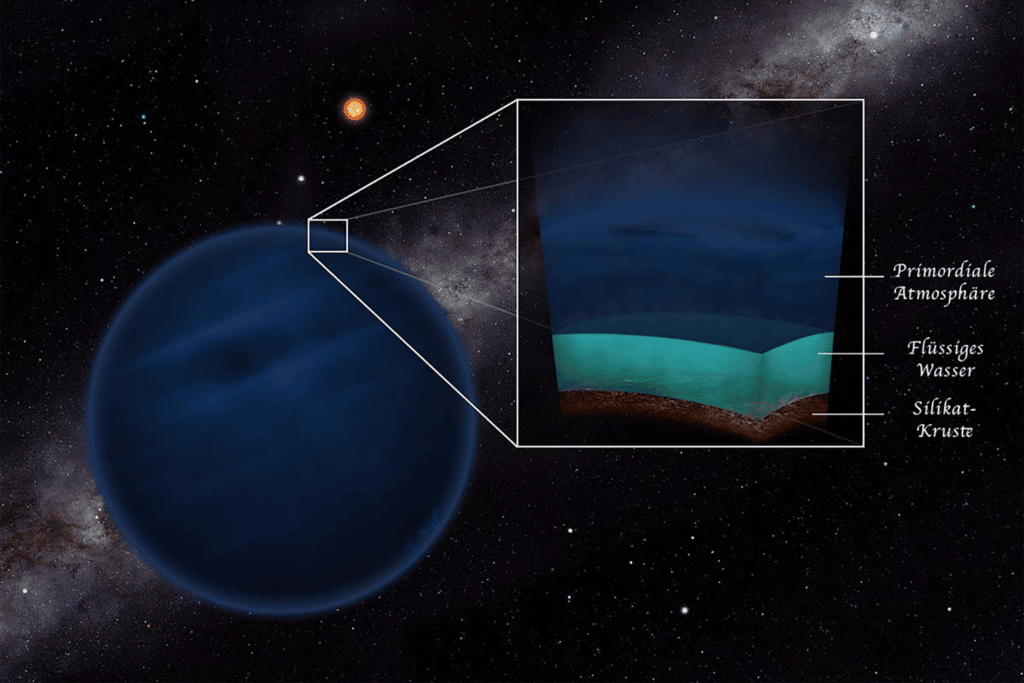

It depends on the mass of the planet and how far away it is from its star, she explains. The Swiss team used a numerical model to investigate the evolution of such giant waterworlds.

“Rocky exoplanets with atmospheres dominated by hydrogen and helium can sustain liquid water on their surface for billions of years,” adds Lous. “It suggests even planets with very different atmospheres from ours can be potentially habitable for long periods of their history.”

Hydrogen and helium were readily available in the disk of materials around young stars, Atmospheres of all planets were dominated by them. In our solar system, small rocky planets like Earth lost this primordial soup in favor of heavier elements like oxygen and nitrogen.

“But large rocky exoplanets at some distance from their star could retain their hydrogen and helium-dominated atmospheres,” says Lous.

An atmosphere is what makes life on Earth possible, regulating our climate and sheltering us from damaging cosmic rays. The study, published in the journal Nature Astronomy, narrows down exoplanets that are most likely to be hospitable.

The emergence of life as we know it is generally understood to require three building blocks: an energy source, access to nutrition and the presence of liquid water. Apart from these requirements, it remains unknown to what extent conditions on other planets need to resemble Earth to be habitable,” the authors write in the paper. “Since the possibility of solar system exploration, habitable conditions are considered on planets and moons that have liquid water oceans underneath a layer of ice. These habitats would have to be inhabited by organisms that are adapted to high pressures and use a metabolism independent of photosynthesis.

“Such organisms have already been found on Earth,” the paper continues. “While today the majority of Earth’s biomass is concentrated on its surface due to complex photosynthetic organisms such as land plants, the subsurface biomass probably outweighed the surface biomass for most of geologic history.

“In the search for life on extraterrestrial planets, it needs to be considered that life might manifest and thrive under conditions that would be considered extreme on Earth.”

A number of prime candidates have already been identified. They will be investigated by the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) which was launched on Christmas Day. They orbit red dwarf stars between 35-150 light years away, close by astronomical standards.

It is believed planned JWST observations of the most promising — known as K2-18b — could lead to the detection of one or more biosignature molecules. By the end of the decade it will be complemented by the ELT (European Large Telescope) and the extremely powerful SKA (Square Kilometre Array).

The ELT will with its 39-meter mirror be the biggest optical telescope in the world and will observe the atmospheric conditions of exoplanets outside the solar system.

“Cold super-Earths that retain their primordial, hydrogen and helium dominated atmosphere could have surfaces that are warm enough to host liquid water,” the study says. “The results suggest habitable conditions may be very different from what we are used to on Earth. We need to remain open-minded when investigating habitability on other planets.”

While the research is certainly thrilling for those hopeful to find life beyond Earth, co-author Christoph Mordasini, a professor of theoretical astrophysics at the University of Bern and a member of the NCCR PlanetS, says the paper’s conclusions “should be considered with a grain of salt.”

“For such planets to have liquid water for a long time, they have to have the right amount of atmosphere. We do not know how common that is,” he explains. “And even under the right conditions, it is unclear how likely it is for life to emerge in such an exotic potential habitat. That is a question for astrobiologists. Still, with our work we showed that our Earth-centred idea of a life-friendly planet might be too narrow.”

More than 4,000 exoplanets have been discovered so far. There are an estimated billion trillion stars in the universe.

Report by Mark Waghorn, South West News Service