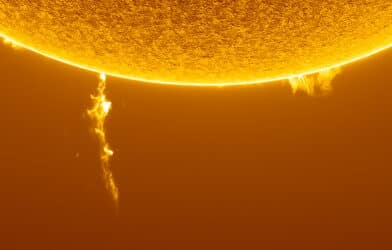

Researchers have detected an ozone-like chemical in the atmosphere of an exoplanet where iron rains from the sky. The thick clouds encasing this alien planet interact with the light from its parent star, creating a compound known as vanadium oxide. This is the first instance of the metallic element being identified on an exoplanet.

This chemical interaction echoes the formation of Earth’s ozone layer, which shields us from the Sun’s damaging ultraviolet radiation.

“This molecule plays a similar role to ozone in Earth’s atmosphere: it is extremely efficient at heating up the upper atmosphere,” explains Stefan Pelletier, the study’s lead author and a Ph.D. student at Montreal University in Canada, in a media release. “This causes the temperatures to increase as a function of altitude, instead of decreasing as is typically seen on colder planets.”

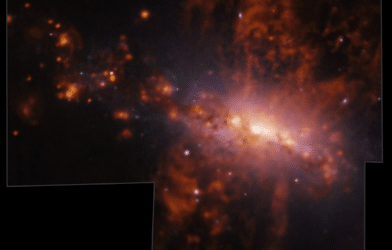

WASP-39b is a gas giant located 634 light-years away within the constellation Pisces. Its close proximity to its parent star—merely 4.3 million miles, approximately twelve times closer than Mercury is to the Sun—results in scorching surface temperatures exceeding 4,400°F. This heat is intense enough to vaporize iron, which then falls during 10,000 mph windstorms.

In the detailed study, researchers identified eleven chemical elements in the planet’s atmosphere. Some of these elements, essential in the formation of rock, have not been detected even in Jupiter or Saturn. The research team utilized a scanner on the Gemini-North Telescope, situated near Hawaii’s Mauna Kea volcano summit.

“Truly rare are the times when an exoplanet hundreds of light years away can teach us something that would otherwise likely be impossible to know about our own Solar System. This is the case with this study,” says Pelletier.

With a mass akin to Jupiter, but nearly six times larger in volume, WASP-39b is often described as “quite puffy.” The Wide Angle Search for Planets (WASP) program discovered it a decade ago.

“We recognized that the powerful new MAROON-X spectrograph would enable us to study the chemical composition of WASP-76 b with a level of detail unprecedented for any giant planet,” notes Bjorn Benneke, a professor from Montreal and co-author of the study.

The study unveils new insights into the presence and abundance of rock-forming elements in giant planets, much like those in our cosmic neighborhood. On cooler planets like Jupiter, these elements reside deeper in the atmosphere, making them undetectable.

Many elements present in the exoplanet’s atmosphere—including manganese, chromium, magnesium, vanadium, barium, and calcium—closely match those found in its host star and our own Sun. These elements were originally formed in the Big Bang, subsequently undergoing billions of years of stellar nucleosynthesis, leading scientists to observe roughly the same composition in all stars. This composition differs, however, from that of rocky planets like Earth, which have a more complex formation process.

The study’s findings suggest that giant planets might retain a composition reflecting that of the protoplanetary disk from which they originated. Certain elements, however, were found to be depleted in the planet compared to its star.

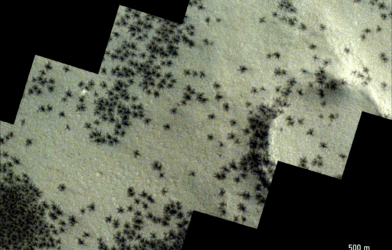

“These elements that appear to be missing in WASP-76 b’s atmosphere are precisely those that require higher temperatures to vaporize, like titanium and aluminium. Meanwhile, the ones that matched our predictions, like manganese, vanadium, or calcium, all vaporize at slightly lower temperatures,” Pelletier elaborates.

Elements’ state—gas or liquid—depends on their condensation temperature. If they exist in a gaseous form, they remain in the upper atmosphere, absorbing light and becoming detect

The study is published in the journal Nature.

South West News Service writer Mark Waghorn contributed to this report.