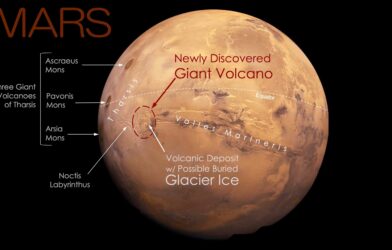

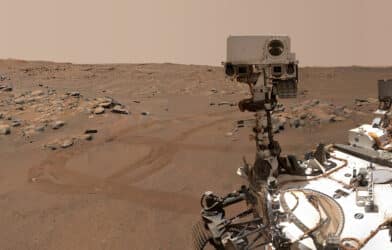

Could some mammals be capable of surviving on Mars? New research suggests it might just be possible. In a stunning twist that expands our understanding of the resilience of mammalian life, researchers have discovered evidence of mice living and thriving where they were once thought not to survive. The location: high on the summits of volcanoes in the Puna de Atacama, a region that mimics the harsh conditions of the Red Planet.

This extreme elevation, more than 6,000 meters above sea level, was deemed impossible for mammalian life due to thin atmosphere and freezing temperatures. The revelation defies previous beliefs about the physiological limits of small mammals.

“The most surprising thing about our discovery is that mammals could be living on the summits of volcanoes in such an inhospitable, Mars-like environment,” said senior author Jay Storz, a biologist at the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, in a statement.

The groundbreaking discovery occurred when Storz and his colleagues first encountered a mummified mouse by chance on the summit of Volcán Salín, located at the edge of a rock pile. This initial find led to a systematic search across 21 Andean volcanoes, 18 of which boast elevations over 6,000 meters. The team uncovered 13 mummified mice in total across these towering summits.

“These are basically freeze-dried, mummified mice,” Storz explained, emphasizing the extraordinary nature of the discovery.

Radiocarbon dating techniques revealed that most of these high-altitude mouse mummies were relatively recent, with some being a few decades old and the oldest being at most 350 years old. This timeline effectively dispels earlier theories that the mice could have been transported to these heights by ancient civilizations such as the Incas, as none of the mummies were old enough to have co-existed with them.

The genetic analysis identified these hardy creatures as a species of leaf-eared mouse called Phyllotis vaccarum, which also populates lower elevations in the region. The comprehensive study showed no genetic divergence between these high-climbing mice and their lower-dwelling relatives, suggesting a shared lineage.

“Our genomic data indicate no: that the mice from the summits, and those from the flanks or the base of the volcanoes in the surrounding desert terrain, are all one big happy family,” Storz added in a Nebraska media release. This genetic unity strengthens the argument that these mice ascended the volcanoes independently, driven by factors still unknown to scientists.

The researchers are puzzled by how these small mammals manage to survive in such barren, freezing conditions with limited oxygen. “It just boggles the mind that any kind of animal, let alone a warm-blooded mammal, could be surviving and functioning in that environment,” Storz expressed, in awe of these resilient creatures.

Further investigations are underway to uncover whether these mice possess unique physiological adaptations enabling their high-altitude survival. Storz’s team, in collaboration with researchers in Santiago, Chile, have initiated experiments involving leaf-eared mice collected from various altitudes, simulating the extreme conditions of the Puna de Atacama to identify any special survival traits.

Yet, one of the most baffling questions remains: why would these mice venture to such formidable heights? While escaping the threat of predators is a plausible motive, the harsh realities of their volcanic habitats, including scarce food and water, pose a new set of life-threatening challenges.

“But why they’re ascending to these extreme elevations is still a mystery,” noted Storz.

As scientists continue their mountaineering biological surveys across the high Andean peaks, each step brings them closer to deciphering the mysteries of life in the most unexpected places, reminding us of nature’s remarkable adaptability.

The research is published in the journal Current Biology.