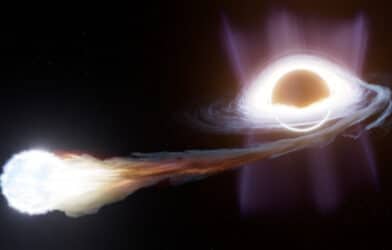

If only we could get weather forecasts this accurately on Earth. An international team of astronomers were able to use NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) to map weather on a scorching planet 280 light-years away. The planet, known as WASP-43b, is a type of world called a “hot Jupiter” — a gas giant similar in size to Jupiter but orbiting much nearer to its sun, resulting in scorching temperatures.

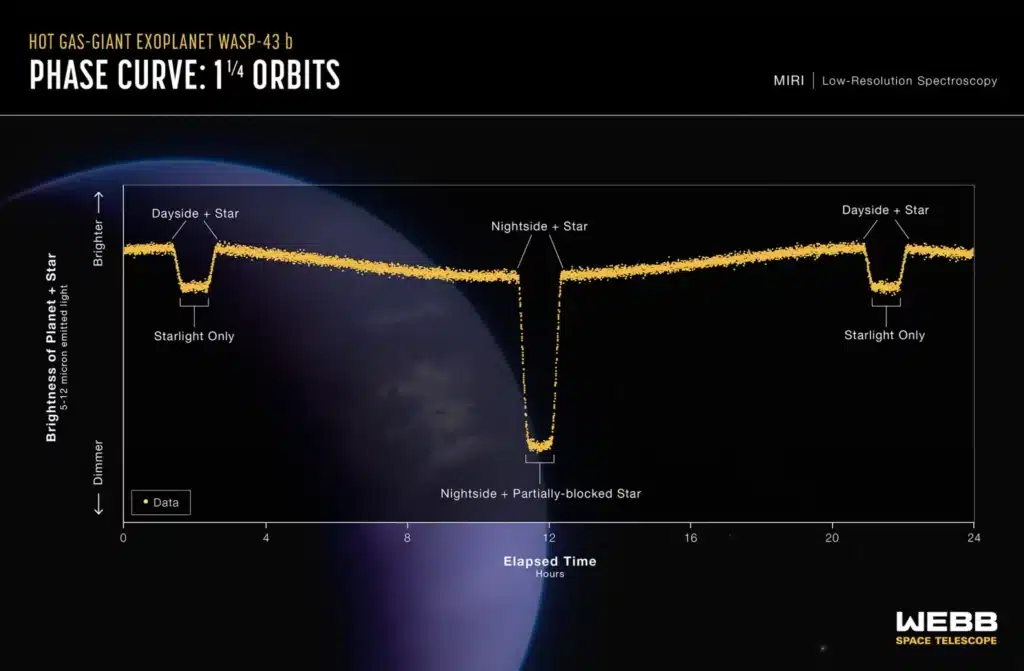

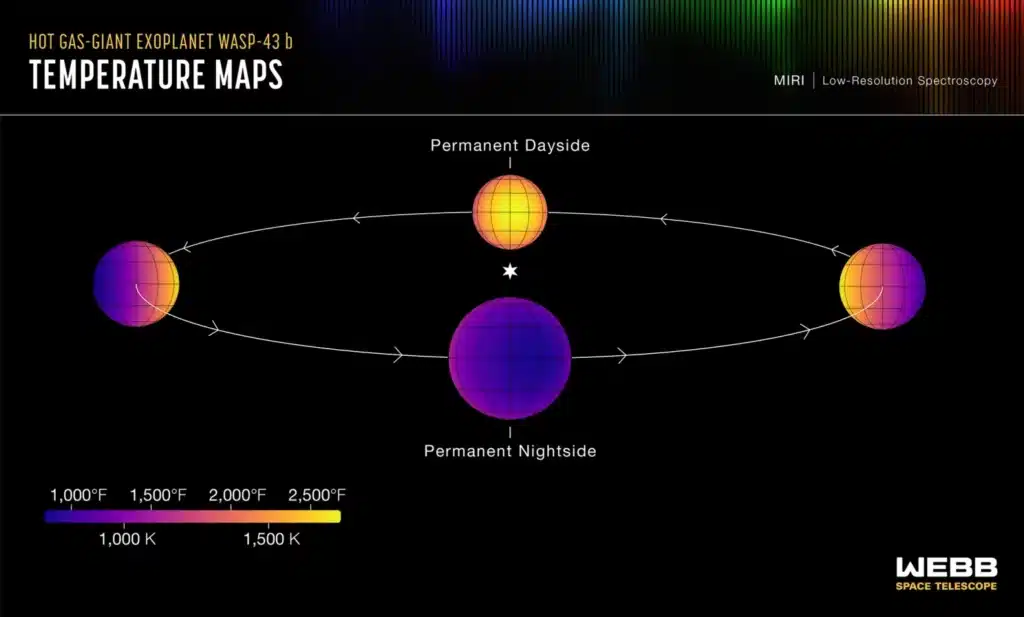

By observing WASP-43b throughout its rapid 19.5-hour orbit, astronomers were able to map out how temperatures and cloud cover vary across the planet’s surface. In the study published in the journal Nature Astronomy, researchers discovered that while the planet’s dayside facing the star is a blistering 2,700 degrees Fahrenheit on average, the nightside dips to a comparably frigid 1,500 degrees Fahrenheit. This dramatic temperature difference between the permanent day and night sides is even more extreme than previous observations had indicated.

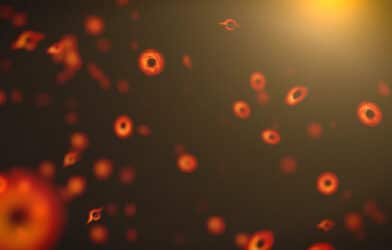

Even more intriguing to astronomers, the JWST data strongly suggests that clouds blanket much of WASP-43b’s cooler nightside hemisphere while remaining largely absent on the dayside. On Earth and most planets in our solar system, clouds are typically composed of water vapor, but on a planet as hot as WASP-43b, minerals like magnesium silicates are thought to condense into clouds at the high altitudes probed by JWST.

“With Hubble, we could clearly see that there is water vapor on the dayside. Both Hubble and Spitzer suggested there might be clouds on the nightside,” says lead study author Taylor Bell, researcher from the Bay Area Environmental Research Institute, in a media release. “But we needed more precise measurements from Webb to really begin mapping the temperature, cloud cover, winds, and more detailed atmospheric composition all the way around the planet.”

Although the presence of nightside clouds was hinted at in earlier studies, JWST’s crisp infrared vision provides the clearest evidence yet for this atmospheric phenomenon. Complex computer models that simulate the atmospheres of hot Jupiters like WASP-43b are able to reproduce the observed cloud patterns and day-night temperature contrasts, but only when clouds are included in the models. Cloudless models, in contrast, fail to match the data as well.

WASP-43b’s wild temperature swings also have major implications for its atmospheric chemistry. Many common molecules like water vapor (H2O), carbon monoxide (CO), and methane (CH4) should be abundant on the hot dayside, but will tend to condense into clouds or chemically react to form other compounds on the cooler nightside.

In what surprised astronomers, JWST did not detect any methane on WASP-43b’s nightside, even though it should be plentiful there based on the measured temperatures and pressures. Researchers believe that fierce winds whipping around the planet are stirring up the atmosphere and preventing methane from forming in the expected amounts. This chemical disequilibrium suggests that hot Jupiters have even more chaotic atmospheres than scientists had imagined.

The JWST observations also confirm the existence of water vapor at all longitudes on WASP-43b, in line with previous studies. However, some details in the spectrum remain puzzling to theorists. All of the state-of-the-art computer models, even when accounting for 3D temperature gradients, atmospheric circulation, and cloud formation, still have difficulty fully explaining JWST’s crisp data.

This means there are key pieces of atmospheric physics that the models are still missing. Processes like cloud microphysics and disequilibrium chemistry may be even more complex than currently assumed. Bell sees this as an exciting challenge, as ongoing observations with Webb Telescope will allow scientists to probe these poorly understood phenomena in greater depth than ever before.

“The fact that we don’t see methane tells us that WASP-43b must have wind speeds reaching something like 5,000 miles per hour,” explains study co-author Joanna Barstow, from the Open University in the United Kingdom. “If winds move gas around from the dayside to the nightside and back again fast enough, there isn’t enough time for the expected chemical reactions to produce detectable amounts of methane on the nightside.”

Though WASP-43b itself is far too hot to be habitable, it serves as an archetype of how gas giant planets evolve and behave under extreme conditions not found in our solar system. As JWST continues to push the envelope of exoplanet science in the coming years, comparative studies of strange new worlds like WASP-43b will be essential for unraveling the formation and diversity of planetary atmospheres throughout the cosmos.