‘We are left with something going on that we don’t completely understand.’

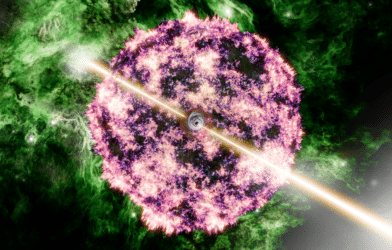

NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope has captured something that has never been seen before. Astronomers discovered the bright red supergiant star Betelgeuse literally blew its top in 2019, losing a large part of its visible surface and producing an enormous Surface Mass Ejection (SME).

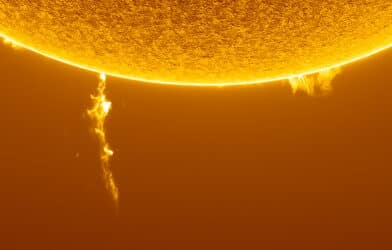

The Betelgeuse SME blasted off an astonishingly 400 billion times as much mass as a typical Coronal Mass Ejection of the sun.

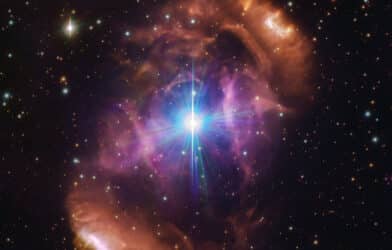

“Betelgeuse continues doing some very unusual things right now; the interior is sort of bouncing,” says Andrea Dupree, of the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard and Smithsonian, in a media release.

Even though the star suffered a catastrophic upheaval, astronomers do not believe Betelgeuse is about to blow up anytime soon. Astronomers are examining the star’s erratic behavior before, after and during the eruption.

“We’ve never before seen a huge mass ejection of the surface of a star,” explains Dupree. “We are left with something going on that we don’t completely understand. It’s a totally new phenomenon that we can observe directly and resolve surface details with Hubble. We’re watching a stellar evolution in real time.”

Astronomers believe the blast was possibly caused by a convective plume, more than 1 million miles across, which bubbled up from deep inside the star. It then generated shocks and pulsations that blasted off a portion of the photosphere. It left the star with a large cool surface area under the dust cloud that was caused by the cooling piece of photosphere. Betelgeuse continues to struggle to recover from the explosion.

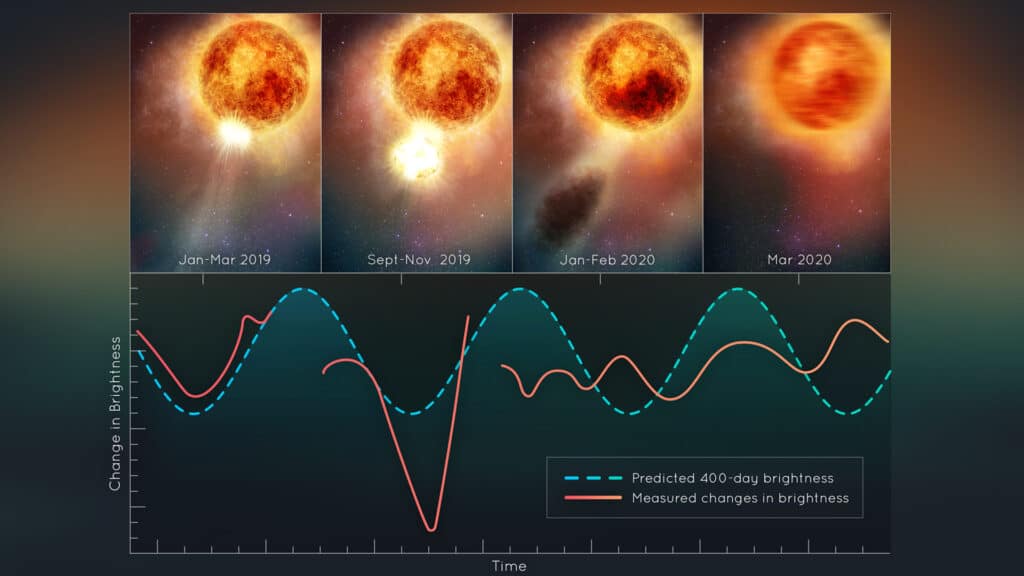

The fractured piece of photosphere is enormous as it weighs several times as much as the moon. It raced off into space and cooled to form a dust cloud that blocked light from the star as seen from Earth. The dimming began in late 2019 and lasted for a few months.

Study authors say Betelgeuse’s 400-day pulsation rate has vanished, maybe temporarily. Astronomers have measured the pulsation for nearly 200 years. Its disruption reveals the brutality of the blast.

Even through the star’s outer layers may be back to normal, the surface is still bouncing around like jello as the photosphere rebuilds itself. Dupree believes the star’s interior convection cells, which drive the regular pulsation, may be sloshing around like an imbalanced washing machine.

Astronomers have never observed such a vast amount of a star’s visible surface get blasted into space. Because of this, it suggests surface mass ejections and coronal mass ejections from the sun may be different events.

The study is published in The Astrophysical Journal.

Simple, they caught a star farting.