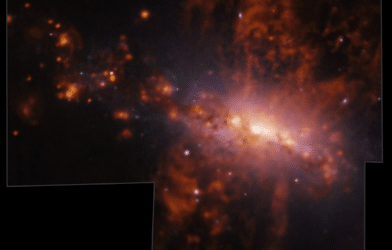

A team of astronomers has captured images of two million far-off galaxies, supermassive black holes, and stars. This discovery will contribute to creating the most comprehensive and detailed three-dimensional map of the universe to date.

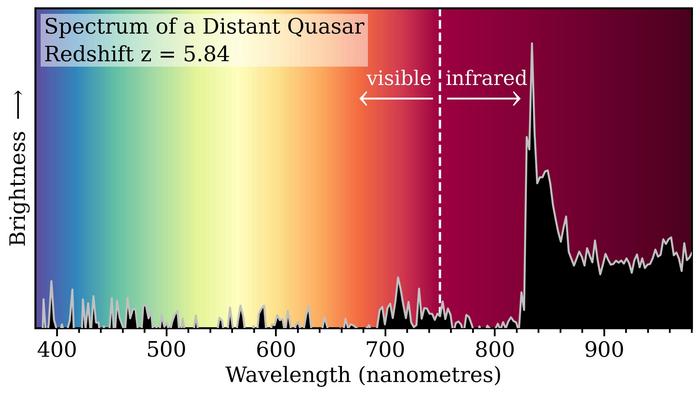

The team observed the spectra of these celestial bodies, which is the breakdown of light into different colors or wavelengths. This reveals the rate of expansion of the universe and offers new insights into the physical properties of cosmic bodies, including our own galaxy, the Milky Way.

The team utilized the powerful DESI telescope (Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument) to identify these distant objects. The images were taken from more than 3,500 exposures of the night sky over a period of six months. The aim is to eventually chart over 40 million galaxies, stars, and quasars.

The initial 80-terabyte dataset, which contains the two million spectra, originates from these thousands of exposures of the night sky.

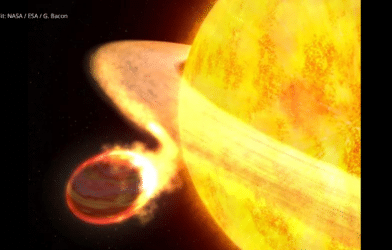

The ultimate goal is to understand dark energy, an elusive force often described as the ‘opposite of gravity.’ DESI, with its 5,000 robotically-controlled mini-telescopes, can analyze light from over 100,000 galaxies in a single night, setting a new world record.

“The fact that DESI works so well and that the amount of science-grade data it took during survey validation is comparable to previously completed sky surveys, is a monumental achievement,” says Dr. Nathalie Palanque-Delabrouille, a DESI spokeswoman and a scientist from the Berkeley Lab in California, in a media release.

The innovative fiber optic system within DESI divides light from celestial objects like galaxies, quasars, and stars into narrow color bands. This process reveals the objects’ chemical compositions, as well as their distance and speed.

The newly captured data will provide fresh insights into dark matter, the unseen substance that binds the universe together. Additionally, it will shed light on the evolution of the universe by examining quasars, the brightest objects in space, and black holes going back 11 billion years in time.

“There are some well-trodden spots where we’ve drilled down into the sky,” says Stephen Bailey, a scientist at Berkeley Lab who leads data management for DESI. “We’ve taken valuable spectroscopic images in areas that are of interest to the rest of the community, and we’re hoping that other people will take this data and do additional science with it.”

Installed at the Nicholas U Mayall four-meter telescope at the Kitt Peak National Observatory near Tucson, Arizona, DESI is two years into its five-year run and already ahead of schedule. The survey has logged over 26 million astronomical objects, with more than a million being added each month.

The early data from the DESI project is now freely accessible through the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC).

South West News Service writer Mark Waghorn contributed to this report.