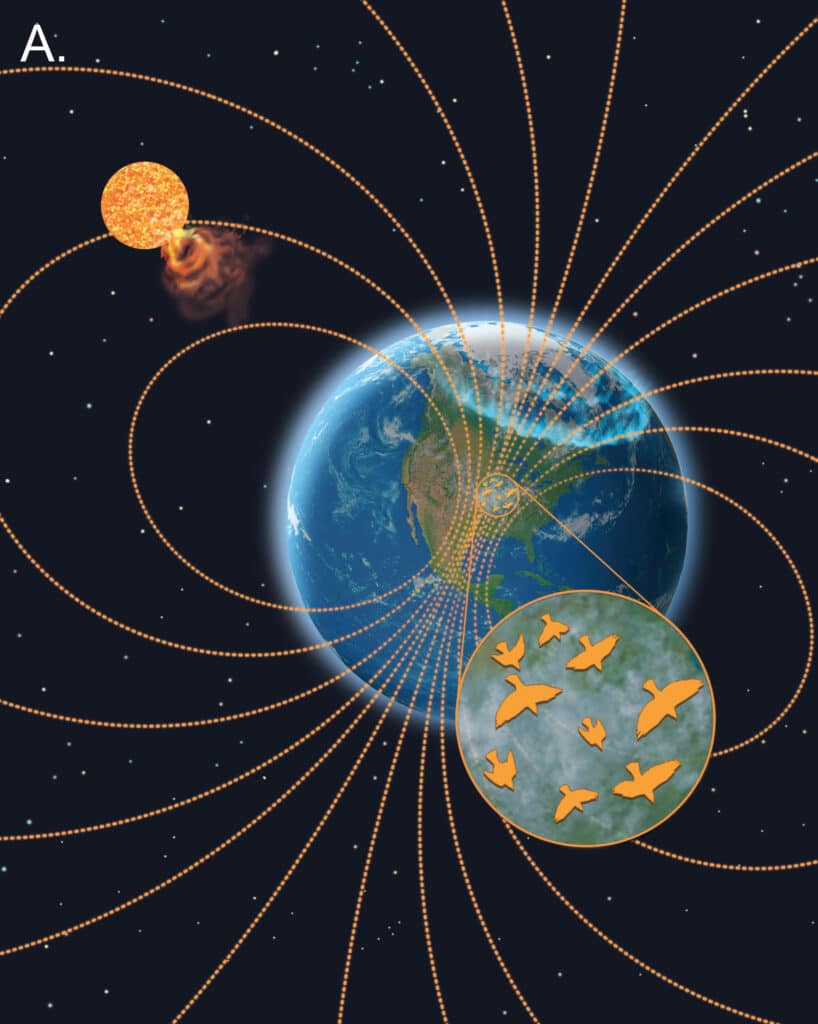

For millennia, birds have taken to the skies, navigating vast distances with precision to find breeding grounds or escape harsh winters. One long-standing mystery: where does their traveling know-how come from? A widely accepted theory is that birds tap into Earth’s magnetic field for their navigational needs. But what happens when this annual spectacle collides with the unpredictable forces of space?

A recent study from the University of Michigan delves deep into this question, revealing surprising insights.

The Magnetism of Migration

Earth’s magnetic field is like an invisible net, shaped by the planet’s molten core and its interactions with the sun. Occasionally, solar outbursts cause disruptions to this field, leading to the dazzling display of northern and southern lights. While beautiful, these outbursts can disrupt satellite communications, power grids, and human navigation systems.

But how do they affect our feathered friends?

The researchers used extensive data from Doppler weather radar stations and ground-based magnetometers, which measure magnetic field intensity. This data helped to explore the link between these geomagnetic disturbances and bird migration.

The result: during severe space weather events, bird migration dropped by 9%-17%, both in spring and fall. The birds that did embark on their journey seemed to have trouble navigating, especially during overcast autumn nights.

Birds in the Balance

Eric Gulson-Castillo, the lead author of the study, emphasizes how sensitive animals are to their environment. “Our findings highlight how animal decisions are dependent on environmental conditions—including those that we as humans cannot perceive,” he says in a statement. This shows that, indirectly, space weather affects not only technological systems but also natural biological systems.

Moreover, these findings build on previous research. While past studies gave us glimpses into birds getting lost during migration due to magnetic disturbances, this new study paints a broader picture. It used a whopping 23-year dataset from the U.S. Great Plains, revealing impacts at the population and landscape levels.

The area in focus, the central flyway of the U.S. Great Plains, spans from Texas to North Dakota. This vast expanse sees a diverse range of birds, from thrushes and warblers to sandpipers, ducks, and geese. The NEXRAD radar scans used by the team could estimate the number of birds and their flight direction.

Winds of Change

One surprising finding was how birds reacted to these disturbances. They seemed to go with the flow, quite literally. During geomagnetic disruptions in fall, birds drifted with the wind more often than battling it. The researchers believe that a mix of magnetic field disruptions and lack of clear celestial cues made navigation harder.

Ben Winger, a senior author, ties these findings to decades of research on how animals perceive magnetism. “Our results provide ecological context for decades of research on the mechanisms of animal magnetoreception,” he says.

The next time you see a flock of birds navigating the skies, remember that they’re tapping into a global navigation system older than any GPS, one that’s vulnerable to the whims of the sun and the cosmos.

The research paper is published in the journal PNAS (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America).

.