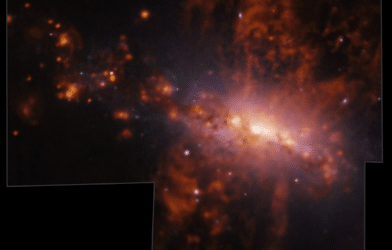

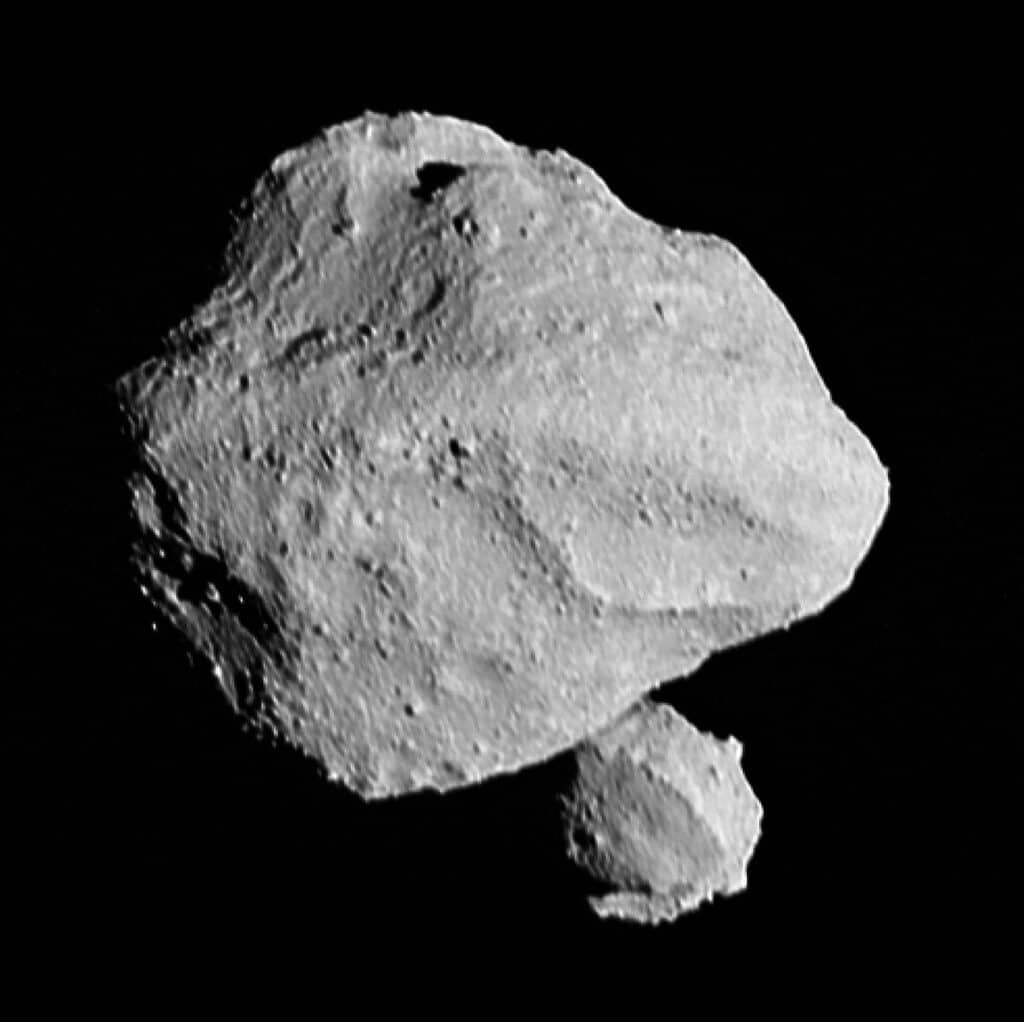

NASA’s ambitious Lucy mission has just provided a galactic surprise. In a historical first, the Lucy spacecraft has captured images of not one, but two asteroids during its flyby on November 1st. What was thought to be a single small main belt asteroid named Dinkinesh is, in fact, a binary pair—a duo of space rocks orbiting each other.

A binary asteroid system is like a cosmic dance between two space rocks gravitationally bound to each other. It’s a rare sight, and Dinkinesh has provided scientists with a golden opportunity to study such a system up close. The larger of the pair measures about 0.5 miles across, while its smaller partner is roughly 0.15 miles wide.

“Dinkinesh really did live up to its name; this is marvelous,” says Hal Levison, Lucy’s principal investigator from the Boulder, Colorado, branch of the Southwest Research Institute, in a statement. The name “Dinkinesh” holds a fitting meaning in Amharic, the language of Ethiopia, translating to — as Levison noted, “marvelous.” This discovery indeed adds a touch of wonder, as it wasn’t just the anticipated single asteroid but a pair that flew by Lucy’s lenses.

But this event wasn’t just about pretty pictures. It served as a critical test for the spacecraft’s systems, especially its terminal tracking system. This technology is designed to keep the spacecraft’s instruments focused on rapidly moving targets—like asteroids whizzing by at 10,000 miles per hour.

“This is an awesome series of images. They indicate that the terminal tracking system worked as intended, even when the universe presented us with a more difficult target than we expected,” says Tom Kennedy, a guidance and navigation engineer at Lockheed Martin.

The flyby wasn’t only a technological exercise. It’s provided a treasure trove of scientific data. Scientists like Keith Noll, Lucy project scientist from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, are intrigued by the binary. “We knew this was going to be the smallest main belt asteroid ever seen up close,” Noll notes. “The fact that it is two makes it even more exciting.”

The dual nature offers a chance to compare it with other known binary asteroids, such as Didymos and Dimorphos, which were observed by NASA’s DART mission.

The data from Dinkinesh is still streaming in and will continue to do so for up to a week after the encounter. This information isn’t just about satisfying scientific curiosity; it’s crucial for the engineers and scientists to assess the spacecraft’s performance and fine-tune it for its next encounter—the main belt asteroid Donaldjohanson in 2025.

This first encounter has been a resounding success for the Lucy mission, setting the stage for future flybys. With a schedule to meet up with the Jupiter Trojan asteroids starting in 2027, Lucy’s journey is just beginning, but if the success of this flyby is anything to go by, the mission promises to deepen our understanding of our solar system’s history and complexity.