We’ve always been told to eat our leafy vegetables, but doing so could have dire consequences in space. Astronauts aboard the International Space Station (ISS) have been able to enjoy fresh lettuce as part of their diet for over three years, thanks to controlled growth chambers on the ISS. However, a new study from the University of Delaware reveals a significant challenge: the risk of contamination from aggressive pathogenic bacteria and fungi — including Salmonella — present on the ISS.

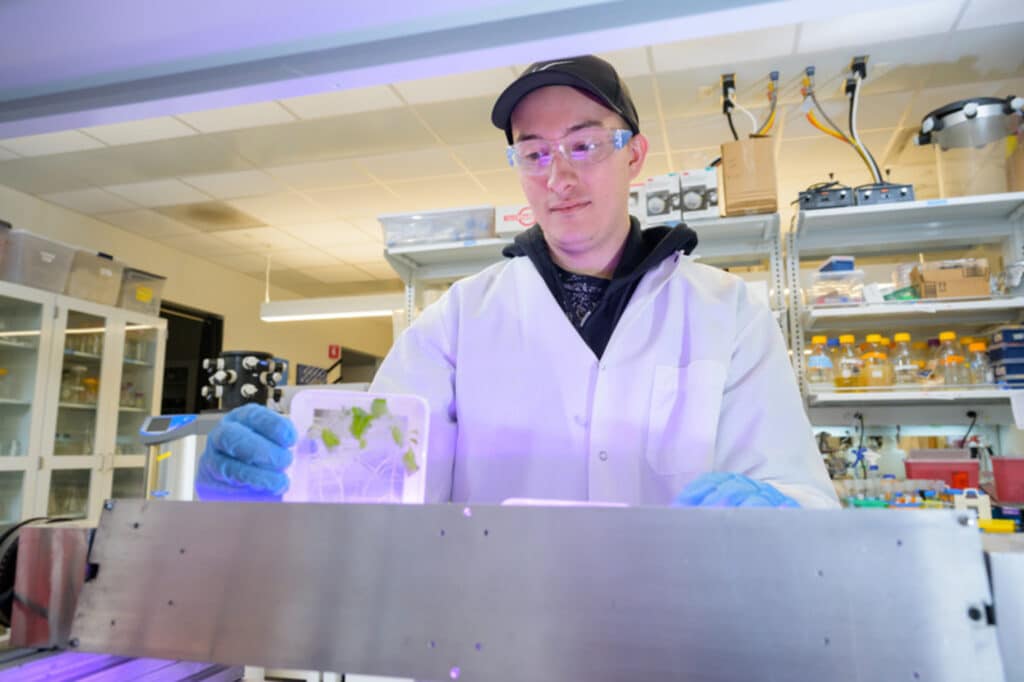

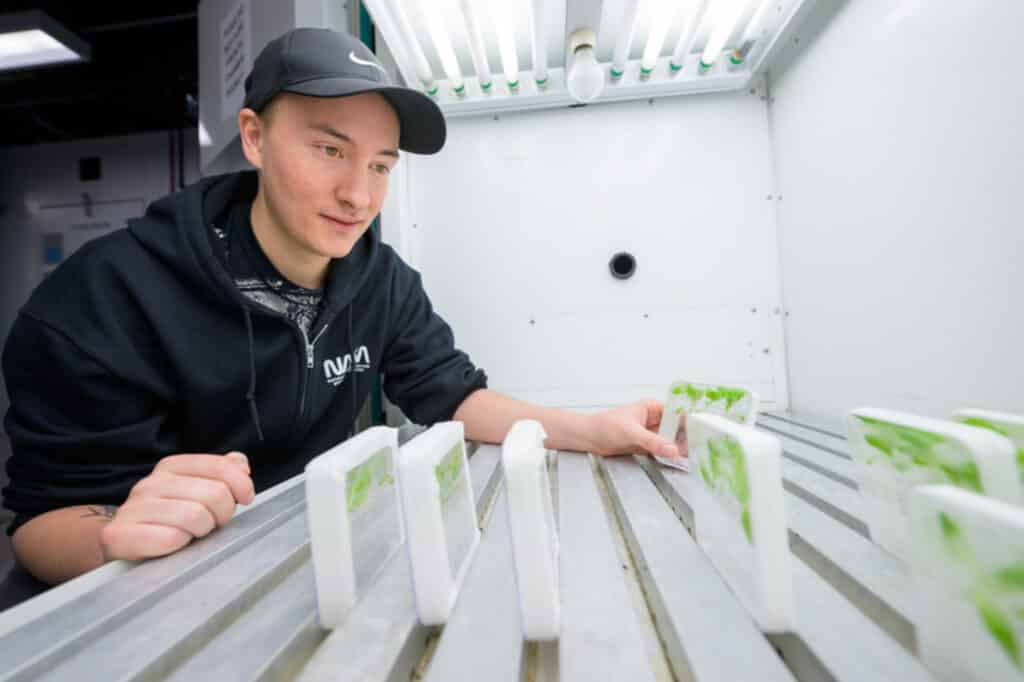

The research involved growing lettuce under simulated weightless conditions like those on the ISS. This process mimicked microgravity by rotating plants, confusing their response to gravity.

“The fact that [stomata] were remaining open when we were presenting them with what would appear to be a stress was really unexpected,” says study lead author Noah Totsline, an alumnus of the University of Delaware’s Department of Plant and Soil Sciences, in a media release.

Stomata are tiny pores on leaves and stems that plants use for respiration. They typically close as a defense mechanism against bacteria. But, in the simulated microgravity conditions, lettuce leaves responded oppositely by opening their stomata, making them more susceptible to infections, particularly from Salmonella.

This discovery is crucial as it suggests that plants grown in space-like conditions may be more prone to pathogenic invasions than those on Earth. Scientists used a device called a clinostat to simulate microgravity.

Researchers also experimented with a helper bacteria, B. subtilis UD1022, which on Earth aids plants in fighting pathogens. Surprisingly, in the simulated microgravity, this bacteria failed to protect the plants, possibly due to an inability to trigger a stomatal closure response in the plants.

Foodborne pathogens are a significant concern aboard the ISS, as microbes are omnipresent and can easily spread in the confined environment.

“We need to be prepared for and reduce risks in space for those living now on the International Space Station and for those who might live there in the future,” notes Kali Kniel, microbial food safety professor at the Delaware Biotechnology Institute. “It is important to better understand how bacterial pathogens react to microgravity in order to develop appropriate mitigation strategies.”

With the Earth’s population projected to reach 9.7 billion by 2050 and 10.4 billion by 2100, according to a United Nations report, and the loss of agricultural land, the need for safe food production in space becomes more critical. Leafy greens, an essential part of astronauts’ diets and relatively easy to grow in hydroponic environments, must be ensured safe for consumption to avoid jeopardizing missions due to food safety outbreaks.

To address the risks, solutions like sterilized seeds and improved plant genetics are being considered. Researchers are evaluating different lettuce varieties under simulated microgravity to understand genetic differences in their responses. This research could lead to genetically modifying plants to reduce the risk of pathogen invasion in space.

“If, for example, we find one that closes their stomata compared to another we have already tested that opens their stomata, then we can try to compare the genetics of these two different cultivars,” explains Harsh Bais, plant biology professor at the University of Delaware. “That will give us a lot of questions in terms of what is changing.”

The findings of this study highlight a unique challenge in space exploration: ensuring the safety of food grown in microgravity environments. As space missions become more prolonged and the idea of living in space becomes a closer reality, understanding and mitigating these risks will be essential for the health and success of astronauts.

The study is published in the journal Scientific Reports.