The mystery of the moon’s geological history is beginning to unravel. Researchers from the Chinese Academy of Sciences used analysis of lunar regolith samples returned by China’s Chang’e-5 mission to get a better understanding of the moon’s secret past. This mission marked the first time in over four decades, since the Soviet Union’s Luna 24 mission in 1976, that lunar samples have been brought back to Earth for study.

The Chang’e-5 probe collected 1.73 kilograms of regolith from the vast expanse known as Oceanus Procellarum, or the Ocean of Storms, returning to Earth with these precious samples in late 2020. Among the significant discoveries within these samples was a new mineral named Changesite-(Y), comprising colorless, transparent columnar crystals, and an intriguing mix of silica minerals.

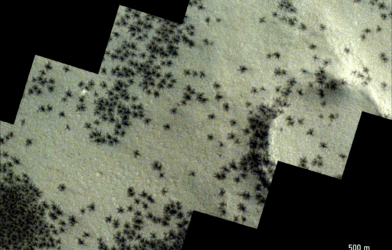

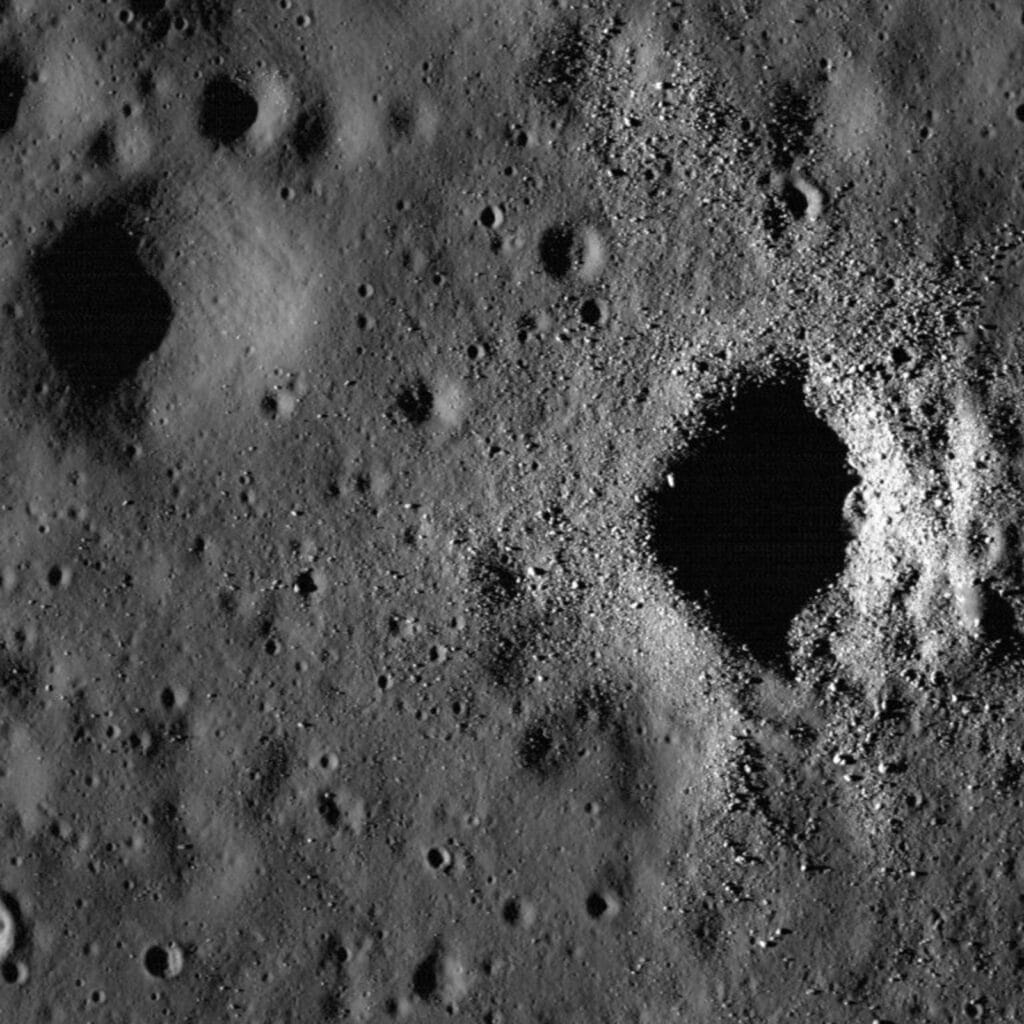

Researchers focused on understanding the process known as impact (shock) metamorphism, a phenomenon that occurs when celestial objects like asteroids and comets collide with the moon at high velocities. Such collisions drastically alter the temperature and pressure conditions on the lunar surface, leading to the transformation of the regolith’s mineral composition and structure. Astronomers particularly noted the presence of silica polymorphs — minerals chemically identical to quartz but differing in crystal structure — such as stishovite and seifertite in the samples.

“Although the lunar surface is covered by tens of thousands of impact craters, high-pressure minerals are uncommon in lunar samples,” says study author Wei Du, from the Chinese Academy of Sciences, in a media release. “One of the possible explanations for this is that most high-pressure minerals are unstable at high temperatures. Therefore, those formed during impact could have experienced a retrograde process.”

Interestingly, the Chang’e-5 samples contained both stishovite and seifertite, which are thought to only coexist under much higher pressures than those estimated for the sample. The presence of these minerals, along with α-cristobalite, suggests a complex formation process involving compression and subsequent temperature increases.

By analyzing the peak pressure and impact duration from the collision that produced these minerals, and incorporating shock wave models, researchers estimated that the resulting crater could range between 3 to 32 kilometers in width, dependent on the impact angle. Further, the study deduced that the silica fragment likely originated from the collision that formed the Aristarchus crater, one of the youngest and most prominent craters identified in the sample’s remote observations.

This analysis not only provides insights into the moon’s past but also showcases the capabilities of modern scientific techniques in deciphering the history of celestial bodies. The Chang’e-5 mission’s success in returning lunar samples has opened new avenues for understanding the moon’s geological processes, including the effects of celestial impacts on its surface composition and structure.

The study is published in the journal Matter and Radiation at Extremes.