From the days of Galileo, scientists have pondered how the moon was formed. Theories have been posited for the last five centuries, but now, a new study is shining light on the moon’s origin story. International researchers have discovered that the moon inherited the indigenous noble gases of helium and neon from Earth’s mantle.

This latest discovery continues to curtail the “Giant Impact” theory that claims the moon was formed by a powerful collision between Earth and another celestial body.

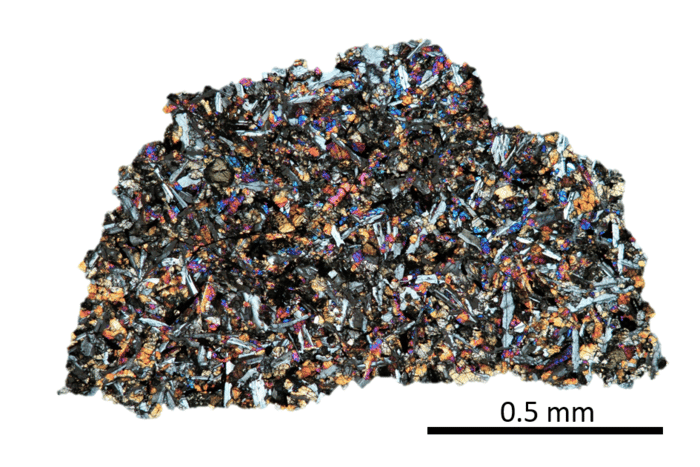

For the study, researchers from ETH Zurich examined six samples of lunar meteorites from NASA’s Antarctic collection. These meteorites are comprised of basalt rock that formed when magma welled up from the moon’s interior and rapidly cooled. Since the meteorites remained covered by additional basalt layers after they were formed, it protected the rock from cosmic rays and solar wind. Lunar glass particles ended up forming during the cooling process.

Researchers say glass particles retained the chemical fingerprints, or isotopic signatures, of the solar gases helium and neon. The gases came from the moon’s interior. Their findings reveal that the moon inherited noble gases indigenous to Earth.

“Finding solar gases, for the first time, in basaltic materials from the moon that are unrelated to any exposure on the lunar surface was such an exciting result,” says Patrizia Will, doctoral student at ETH Zurich, in a media release.

Using a state-of-the-art noble gas mass spectrometer called “Tom Dooley,” like the popular Grateful Dead song, researchers ruled out solar wind as the source of detected gases. There was much more helium and neon than they expected.

“I am strongly convinced that there will be a race to study heavy noble gases and isotopes in meteoritic materials,” explains Henner Busemann, professor at ETH Zurich and one of the world’s leading scientists in the field of extraterrestrial noble gas geochemistry.

Busemann believes researchers will begin looking for noble gases, like xenon and krypton, which are much harder to identify. They will also look for hydrogen or halogens, which are volatile elements, in lunar meteorites.

“While such gases are not necessary for life, it would be interesting to know how some of these noble gases survived the brutal and violent formation of the moon. Such knowledge might help scientists in geochemistry and geophysics to create new models that show more generally how such most volatile elements can survive planet formation, in our solar system and beyond,” explains Busemann.

The study is published in the journal Science Advances.