These moon rocks have been waiting for five decades to see the light of the lab. They’ve been waiting since Apollo 17 returned to Earth on December 1972.

When 254 pounds of rock and regolith (soil) came back, it wasn’t as simple as cracking open the canisters to start researching. Scientists and astronauts at the time realized that some scientific questions would go unanswered during their lifetime. Lunar samples required better equipment, lab conditions, and technology. This way, scientists could safely remove each sample without worrying about damaging it before they could analyze its contents in more detail.

After they arrived on Earth, samples were stored in a chamber where there was no risk of contamination from outside sources. And the samples from Apollo 17 waited 50 years to start answering scientists’ questions.

“We are the first people who got to actually see this soil for the first time,” Gross says in a NASA media release. “It’s just the best thing in the world – like a kid in the candy store, right?”

The process took about four years to figure out and design the unique conditions needed to process the lunar samples. To get the Apollo 17 Moon soil back to researchers in the U.S., scientists had to design and retrofit a facility to process the freezing cold rock and regolith.

The samples were collected by astronauts Harrison Schmitt and Eugene Cernan during their three days on the Moon, which was Schmitt’s only visit to space. The pair spent about 22 hours outside the Lunar Module exploring the Moon and collecting geologic samples.

Rock and soil were stored in a triple-sealed aluminum container, known as an “Apollo Lunar Sample Return Container.” The containers waited to be open on Earth, under controlled conditions in the Lunar Receiving Laboratory at the Houston Manned Space Center.

NASA scientists had a chilly problem transporting the frozen lunar samples to different research facilities around the United States: It needed to be cold (-4 degrees Fahrenheit or -20 degrees Celsius); scientists needed to be able to work with thick gloves in a nitrogen-purged glove box; and the samples needed to be express shipped to research facilities with dry ice.

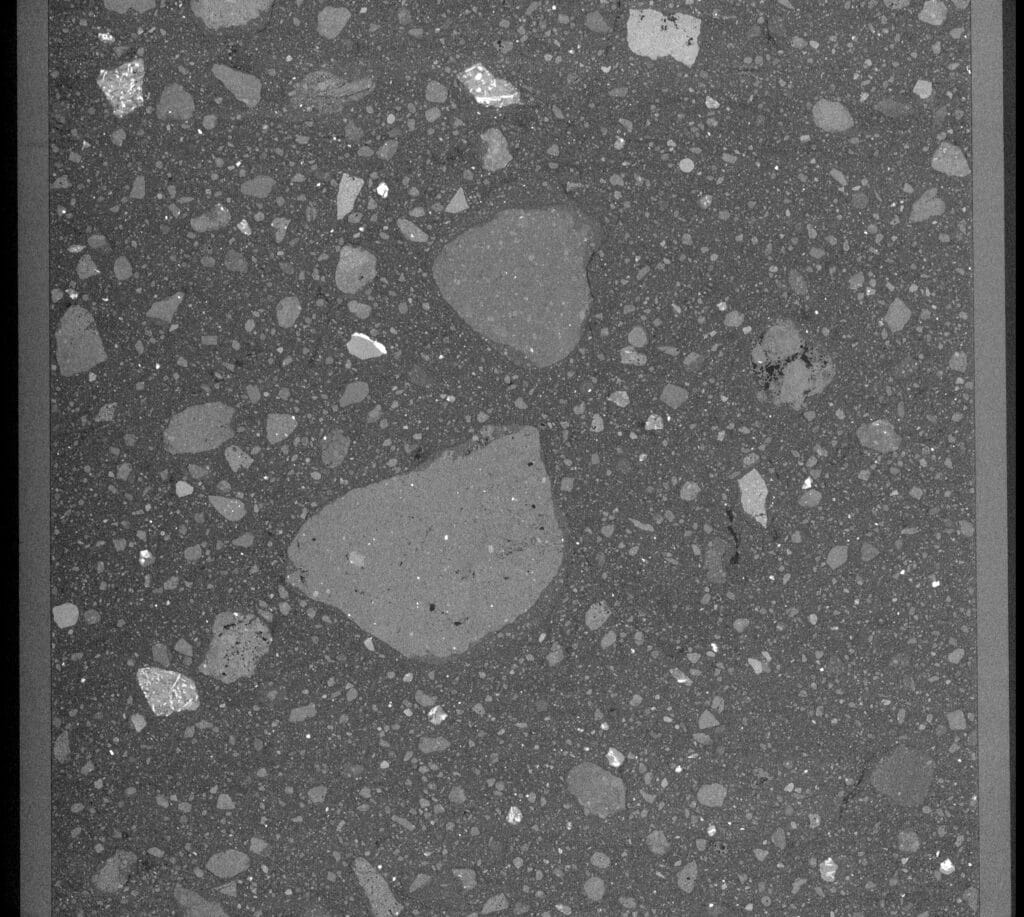

The samples will be tested using a variety of techniques including X-ray CT and scanning electron microscopy. These tests will reveal information about the moon’s chemical composition and mineralogy, which may help answer questions like: What is the makeup of the lunar regolith (soil)? How old are minerals on the surface? Are there variations in composition within different regions of the moon? These are just some examples of what scientists hope to learn about our nearest celestial neighbor.

Jamie Elsila, a research scientist in the Astrobiology Analytical Laboratory at Goddard, is focusing on the study of amino acids in lunar samples, which are essential to life on Earth. “It’s very cool to think about all the work that went into collecting the samples on the Moon and then all the forethought and care that went into preserving them for us to be able to analyze at this time,” she says.

The Apollo samples have provided NASA with a wealth of insights into the moon’s geologic evolution, but new samples from the Artemis missions and beyond hold even more answers for the next generation.

Can you please tell me what was found ‘in’ the core sample from Apollo 17 ? Dust , granules & fines could be in different ‘depths’ , some cores having had from 20 to more than 40 levels.

My research has 27 cores in the 6 Apollo missions. APOLLO 11 had 2 ‘small’ cores of less than 15 cm. Is that true ? Apollo 17 had a few, but the source (in France) states that 3 of the 27 had a thermometer at the end = the findings said ” 3 times too hot , is that true ???

Thank you for your time, if possibly my information is ‘possible’ PM