In a new study, Cornell University astronomers have found that icy comets evolve over time, and their shapes may be more diverse than previously thought.

Comets are small bodies that orbit the sun, usually far from Earth. Their icy nucleus may be as large as a few kilometers in diameter or as small as a few hundred meters across. Comets are sometimes called “dirty snowballs” because they are made up of rock, dust, and ice mixed in various proportions. (That doesn’t mean they’re not beautiful, though.) They’re thought to be remnants of the birth of our solar system, and they can contain organic molecules that might have helped seed life on Earth.

“As some of these comets have been pulled into the inner solar system,” explains Abhinav S. Jindal, a graduate student in astronomy and member of the research group of Alexander Hayes, “their surfaces undergo changes. Science is trying to understand the driving processes.”

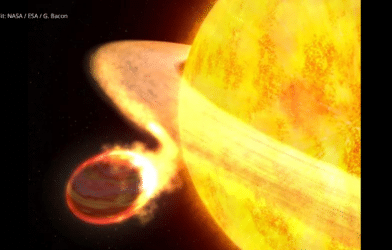

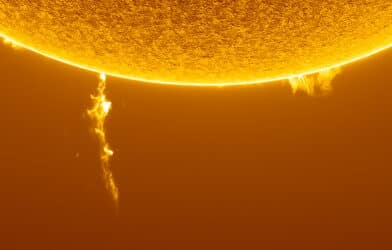

These ancient space rocks have a unique geology that has been shaped by their environment — the sun’s heat and gravitational force — which results in surface features such as smooth terrains.

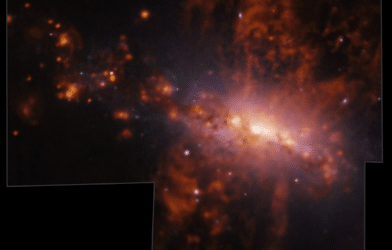

When a comet gets close enough to the sun, some of its ice melts, creating a coma — a cloud of gas and dust around the nucleus (the solid object at the heart of the comet). Comets form tails when their path through space takes them too close to the sun. These tails are made up of charged particles that have been stripped off by solar winds and radiation.

The pressure from solar radiation turns this gas into plasma — an ionized gas that glows brightly in ultraviolet light. This is why comets appear so bright when they pass near Earth.

Researchers examined the evolution of comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko from its formation to the present day with data gathered by the Rosetta mission. European Space Agency’s Philae lander became the first human-made craft to touch down on the comet’s surface after traveling over 500 million miles through space.

It was a tense mission — the lander “bounced” off the comet’s surface twice before landing in an undesirable crevice. Luckily, Philae was able to send some chilling pictures back to Earth.

“The final set of images supplements the rich treasure chest of data that the scientific community are already delving into in order to really understand this comet from all perspectives – not just from images but also from the gas, dust and plasma angle – and to explore the role of comets in general in our ideas of Solar System formation,” says Matt Taylor, ESA’s Rosetta project scientist. “There are certainly plenty of mysteries, and plenty still to discover.”

While some comet surfaces were smooth while others were rough; this unevenness could be due to how long ago each comet last passed through its perihelion (the closest point to the sun). The results suggest that some comets may have been changing shape for billions of years before reaching Earth for observation.

Scientists are looking for the smoothest, flattest surfaces on comets to land spacecraft and gather samples. There’s something about comets that make them seem more Earth-like than other planets in our solar system — and that makes them especially interesting to scientists. Comets are made of water ice and frozen gases (like methane), which means they’re already made of many of the same things we see on Earth.

As you can imagine, there are a lot of challenges in sending a lander to such a quick-moving target that’s so far away.

The research is published in the Planetary Science Journal.